Reviews

Shortly after invading Australia, Arthur Phillip decided that he wanted to go home. The decision was entirely understandable: the broadband speeds were terrible, everyone around him suddenly seemed to want to cheat at every ball game they tried to play, but most of all, the natives kept getting confused by him having two first names, and no last name.

Phillip Arthur was damned if he was going to live out his days in a colony where half the people called him ‘Arthur’ and the other half called him ‘Phillip’.

And so, in December 1792, Arthur Phillip (or was it Phillip Arthur, I can never remember?) ‘convinced’ two Wangal locals by the name of Yemmerrawanne and Bennelong to set sail to London with him.

To Phillip Arthur, Yemmerrawanne and Bennelong were trophies, strange objects won as a reward for conquering a distant land. But we can reveal for the first time that Yemmerrawanne and Bennelong in fact had a different plan about what they wanted to achieve on their trip to this strange land known as ‘England’. This is that story, never before told.

(Extract from Chapter Two of The Completely True History of Australia)

It was May 1793, when their boat finally arrived in England, in the port at Falmouth in Cornwall.

Local authorities twigged that something was awry the moment Yemmerrawanne walked down the plank. He reached into his bag and pulled out a large piece of cloth decorated with local Sydney seashells and beads. It was attached to a long stick.

“I claim,” the strapping young 18-year-old declared, “This land on behalf of the Eora nation.” And with that he planted the handmade flag into the soft Cornwall soil.

“Now hold on a second,” said Phillip, as he walked down the plank behind Yemmerrawanne. “You can’t just claim this land. People already live here.”

“So what you’re saying is that you can’t just hop off a boat, ignore the locals, and then claim land for yourself?” asked Yemmerrawanne. He stared into Phillip Arthur’s eyes.

Arthur Phillip averted Yemmerrawanne’s gaze. “Hmmm. I see what you mean,” he muttered.

****

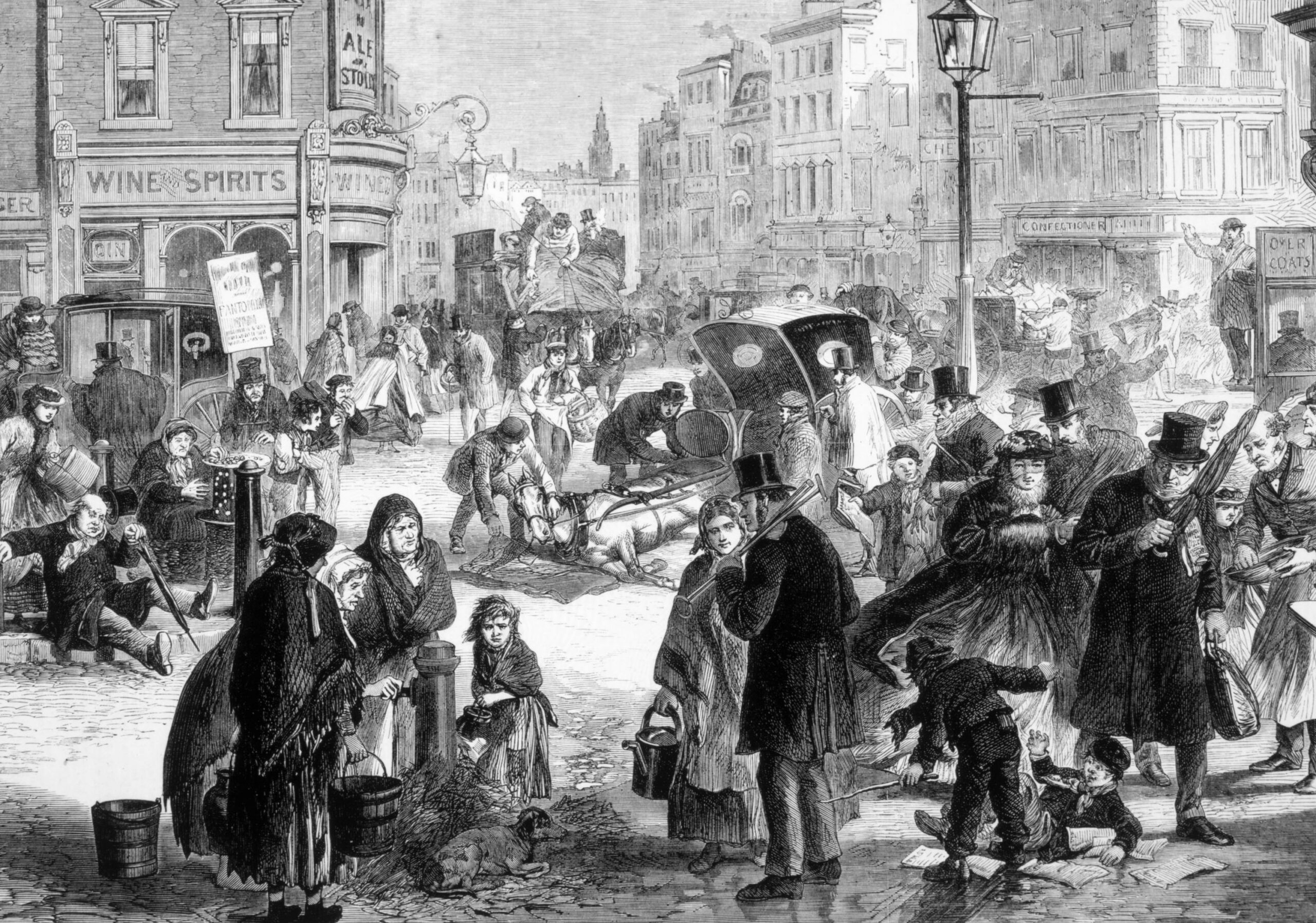

Within days, both Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne had been transported to London, staying at the home of William Waterhouse in the fashionable suburb of Mayfair, for which rent was double because Waterhouse also owned Park Lane.

There the intrepid explorers were fitted with the latest clothes from the indigenous people, and taught how to read and write the local language. Despite this charming hospitality, Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne quickly came to the conclusion that most of the locals had limited knowledge of how to spear fish, were completely unskilled at the use of boomerangs and didn’t know a single clapstick song. It was clear the indigenous English people could not, under any reasonable definition, be considered ‘civilised’ and therefore, the land of England was for all intents and purposes ‘terra nullius’ – vacant land, available to be claimed by the first civilised explorers.

Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne hatched a plan to go around and see whether anything was worth claiming.

One day not long after their arrival in London, the pair headed to a local sacred site known to locals as ‘Westminster Abbey’. For centuries, males had carried out strange rituals involving smoke, robes and harmonious chanting as a means of commemorating the death of local elders. The most important elders were then buried underneath this site as a means of ensuring their safe passage to the afterlife.

While Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne found the belief systems primitive, and strangely linear, with no understanding of the circularity of time and place, they were intrigued by the site.

Arriving at the site, they noticed a crypt marked ‘Sir Isaac Newton’. They knew that Newton was much revered by the current tribes who lived around London.

Taking a small metal jimmy from his bag, Bennelong prised open the large marble crypt, cracking the stonework along several lines. The marble was heavy, so Yemmerrawanne went to work on it with a hammer, smashing the lid into more convenient-sized pieces. Eventually the intrepid explorers were able to get into the crypt, but just as Bennelong was retrieving a small, toothless skull from the box, a man dressed in a long flowing black dress ran over to the two men.

“Er, excuse me! Excuse me! I’m the bishop here. Who are you? What are you doing?” said the man. He seemed agitated. Bennelong suspected that the man was perhaps scared of ghosts, which locals commonly believed were real.

“It’s alright,” chuckled Yemmerrawanne, “We’ll protect you from the ghosts.”

Bennelong laughed too. “Yeah. We’re special ghost warriors. You have no need to be afraid.”

“I’m not scared,” said the bishop. He was close to tears. “You’re not allowed to take those. They’re Isaac Newton’s bones!”

“No. It’s alright, we’re explorers. We’re just digging up these to take them back home to put on display. We’ll do a better job of looking after them that you seem to be doing,” said Yemmerrawanne.

“Yeah,” Bennelong chimed in. “Anyone could just come and take these bones. You clearly don’t care enough to look after them properly. Let us deal with it.”

“But, but…” stammered the bishop. “They’re the bones of our most sacred ancestor.”

Bennelong stared into the eyes of the broken bishop. “So what you’re saying,” he said, “is that explorers can’t just come in, trample on sacred burial grounds, and then take whatever they want with the excuse that they’ll look after them.”

The bishop averted Bennelong’s gaze. “Oh. I see what you mean,” he said.

By late June, Yemmerrawanne started feeling ill. The trip from Australia had been rough going, but compounding the problem was the shock of having to eat a strange, noisome substance that the English called ‘food’.

Further, the two were confounded by the strange customs, the strangest of which was the insistence of the indigenous locals to play a massive game of opposites when it came to talking about the climate.

By now it was late June, the peak of what seemed to be a particularly cold and brutal winter in London. Both Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne were alarmed by the need for a layer of clothing just to stay warm.

But instead of seeking shelter inside, the locals insisted on calling the season ‘summer’ and going outside into the parks and streets, talking about how warm the weather was. There seemed no pay off to this particular eccentricity. “On the topic of the weather, their minds are topsy-turvy. I rather suspect that their minds have been poisoned by their ‘food’,” wrote Bennelong in his diary.

****

Despite Yemmerrawanne’s declining condition, Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne decided to keep exploring the new land.

The next stop was the Tower of London, a place that local tribesmen had told them contained the most highly valued trinkets in the whole nation, owned by the most senior nobles in the land and stored there, on display for over three hundred years, according to local legend.

This was something the explorers had to witness for themselves, but upon arriving in the Jewel Room, the explorers were bitterly disappointed. It was largely a collection of useless rocks of varying colours, attached to soft shiny metals. The rocks weren’t even in useful shapes, and could not be used for cutting or sharpening.

Indeed, Bennelong and Yemmerrawanne both doubted they could be used for anything other than as ornaments to be draped on elder’s bodies and heads during the native’s primitive rituals that they held from time to time, to please the local God.

Nevertheless Yemmerrawanne decided to take a few of the shiny stones back to Australia for further study. Perhaps there was a medicinal property that the natives had missed. He reached through the bars that the stones were behind, and grabbed a large ‘crown’.

The reaction from the strangely dressed local warrior standing nearby was immediate.

“Oi,” said the man, who wore a large black furry head-mask and a blood-red jacket, “They’re our sacred stones.”

“It’s alright,” replied Yemmerrawanne. “I’m just going to study them. It’s not like you’re using them anyway.”

****

By early the next year, Yemmerrawanne was gravely ill. Despite his protests, local witch doctors had performed the local blood-letting, leech treatments, and other rituals that were clearly based on nothing more than superstition. If only, Yemmerrawanne thought, he’d had the foresight to bring fresh food from Australia, he might have been able to survive. As it was, with only English ‘food’ to survive on, there was no hope of making it.

On 17th May, 1793, the 19-year-old could hang on no longer.

****

News of Yemmerrawanne’s death travelled fast among the natives. Within a week, the most senior elder, a short man named King George III, demanded to meet Bennelong. Bennelong, curious as ever, agreed.

As was the local custom, Bennelong went to a special sacred ground, known as Buckingham Palace, where the elder spent much of his time.

Bennelong walked into the Throne Room. At the other end, a short man was sitting on a garish, gold-coloured piece of metal that had spikes all around it. It looked terribly uncomfortable. The man sitting there had covered his face in white powder, some sort of ritual, thought Bennelong, to make himself look like he was dying of cancer. Bennelong had long given up trying to interpret the natives, and had decided to just take them for what they were: profoundly unfit people who had no physical ability to speak of.

Perhaps looking like you were about to die made people respect their elders. Who knew?

Bennelong walked up to the throne, and sat on the spare seat next to the King.

“Get out of there!” yelled the King. “That’s the Queen’s throne!”

Bennelong thought this was a very rude way to treat a guest, but he obliged. He’d learnt that the natives had a habit of making their faces red when they didn’t get their way.

“As the King,” the puny man yelled, still sitting on the chair, “I object to you taking all our sacred objects. Over the past year, you’ve dug up our most sacred site. You’ve taken the bones of our most revered ancestors, you’ve stolen the jewels of our most important nobles. Yesterday, you even stole the Magna Carta, which is the most important document ever created.”

Bennelong had noticed that the natives had a tendency for hyperbole when it came to describing their favourite trinkets. Nevertheless, it was important that Bennelong at least appear to take this little man seriously. Despite his crazed demeanour he was apparently held in high esteem by the tribes in the area.

“I’ll tell you what,” said Bennelong. “Once I get all this stuff home,” he pointed at his bag, which by this point was overflowing with the objects he’d picked up along his way, “I’ll launch an immediate inquiry into how this happened, and once we’ve had a full investigation, we’ll return the things to you that we deem to be important to you. Shouldn’t take more than a couple of hundred years.”

The angry little man stared into Bennelong’s eyes. Bennelong stared back.

“Oh. I see what you mean,” said the King.

This is an extract from Chapter Two of The Completely True History of Australia (Chaser Quarterly, 2018)